Changing Teacher Pension Plans Is a Challenge, Especially if You Want High-Quality Teachers

Nationally, employer costs for public teacher pensions have increased from $530, or 4.8 percent of per-pupil operating expenditures in 2004, to $1312, or 10.7 percent of per-pupil expenditures in 2019. What are these increasing costs buying? In a recent study, Shawn Ni, Michael Podgursky, and Xiqian Wang asked: Would alternative, less costly retirement plans raise or lower workforce quality?

The team used data for Tennessee public school teachers. Traditional teacher retirement plans like the one in Tennessee have strong “pull” and “push” incentives. They “pull” or retain senior teachers to certain combinations of age and experience, and “push” teachers into retirement beyond a certain point.

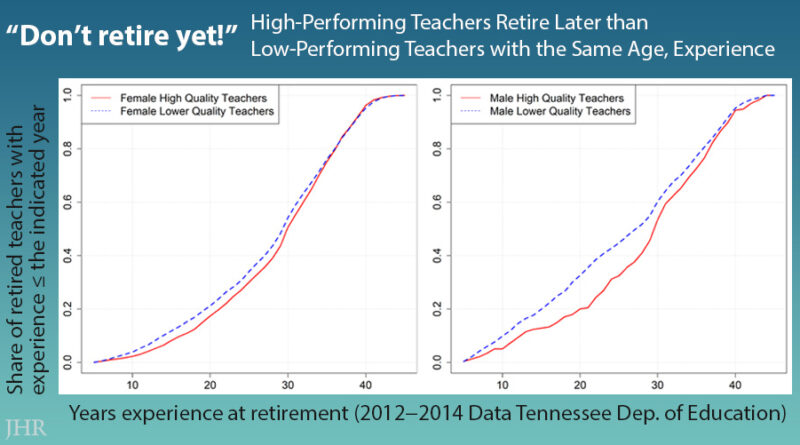

The evidence showed that under current pension rules, teachers in the highest performance category on a statewide assessment tend to retire later than lower performing teachers with the same age and experience (see graph). In order to better understand this, the researchers estimated a model of teacher retirement behavior that captures differences in retirement preferences for high- and low-performing teachers.

The results showed that enhancements to the current plan would raise overall pension costs but lower quality of the senior workforce. By contrast, conversion of all senior teachers to a defined-contribution plan would lower costs and raise workforce quality.

However, state constitutions and court rulings generally preclude a wholesale conversion of teachers from their current to a defined-contribution retirement plan. Thus, the researchers considered targeted retention bonuses ranging from $5000–$20,000 designed to defer retirement of high-performing teachers in high-need schools. This policy would not change the rules of the pension plan for incumbent teachers, but would simply pay a one-time bonus for teachers who reach certain experience milestones.

Is this a cost-effective option for cash-strapped school districts? Because some teachers who take the bonus would have continued working anyway, the simulations show that bonuses tied to certain milestones of experience are more cost-effective. The estimates of the cost per additional teaching year of such a policy ranged from $57,000–58,000 (net of salary) for female teachers and $45,000–$57,000 for male teachers. Given recent estimates of the lifetime value of a high-quality teacher for students, these estimates suggest that retention bonuses could be a cost-efficient strategy to improve student performance in high-poverty schools, as compared to, say, across-the-board pay increases or smaller class sizes, since these would be targeted to the top teachers.

Another plus is that the methods developed in this paper are readily applicable to analysis of teacher pension plans in other states, as well as other potential pension reforms.

Read the study in the Journal of Human Resources: “Teacher Pension Plan Incentives, Retirement Decisions, and Workforce Quality,” by Shawn Ni, Michael Podgursky, and Xiqian Wang.

***

Shawn Ni is a Professor of Economics in the Department of Economics, University of Missouri–Columbia. Michael Podgursky is Chancellor’s Professor of Economics in the Department of Economics, University of Missouri–Columbia and Director, Sinquefield Center for Applied Economic Research, Saint Louis University. Xiqian Wang is an Assistant Professor in the School of Economics and Management, Beijing University of Technology.

The authors thank the Laura and John Arnold Foundation for research support and three referees for valuable suggestions. The usual disclaimers apply. Data are available from the authors.