This blog by Alfred McCoy is re-posted from HISTORY NEWS NETWORK.

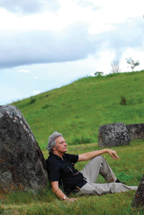

Alfred McCoy is professor of history at the University of Wisconsin–Madison and the author of two recent books on this subject—Torture and Impunity: The U.S. Doctrine of Coercive Interrogation (University of Wisconsin Press, 2012) and A Question of Torture: CIA Interrogation from the Cold War to the War on Terror (2006), as well as a related work, Policing America’s Empire: The United States, the Philippines, and the Rise of the Surveillance State.

Introduction The recent Senate Intelligence Committee’s report on CIA torture is arguably the single most important U.S. government document released to date in this still-young 21st century. Yet even with all its richly revealing detail about the CIA’s recourse to torture since 9/11, the report’s impact on the ongoing U.S. debate over impunity is muted by some serious failings. Above all, the committee’s cursory treatment of Washington’s long, contradictory history with torture renders this report, in certain critical areas, superficial.

No matter what its limitations might be, this Senate report is still an  historic document that will be debated for months and analyzed for years. At its most visceral level, these 534 pages of dense, disconcerting detail takes us into a Dante-like hell of waterboard vomit, rectal feeding, midnight-dark cells, endless overhead chaining, and crippling cold. With its mix of capricious cruelty and systemic abuse, the CIA’s Salt Pit prison in Afghanistan can now join that long list of iconic cesspits for human suffering—Devils’ Island, Chateau d’If, Con Son Island, Robben Island, and many, many more. But perhaps most importantly, these details have purged that awkward euphemism “enhanced interrogation techniques” from our polite public lexicon. Now everyone, senator and citizen alike, can just say “torture.”

historic document that will be debated for months and analyzed for years. At its most visceral level, these 534 pages of dense, disconcerting detail takes us into a Dante-like hell of waterboard vomit, rectal feeding, midnight-dark cells, endless overhead chaining, and crippling cold. With its mix of capricious cruelty and systemic abuse, the CIA’s Salt Pit prison in Afghanistan can now join that long list of iconic cesspits for human suffering—Devils’ Island, Chateau d’If, Con Son Island, Robben Island, and many, many more. But perhaps most importantly, these details have purged that awkward euphemism “enhanced interrogation techniques” from our polite public lexicon. Now everyone, senator and citizen alike, can just say “torture.”

In its most important contribution, the Senate report sifts through some six million classified documents to rebut the CIA’s claim that torture produced important intelligence. All the agency’s assertions that torture somehow stopped terrorist plots or led us to Osama Bin Laden were false, and sometimes knowingly so. Instead of such spurious claims, CIA director John Brennan has now been forced to admit that any link between torture and actionable intelligence is “unknowable.”

Of equal import, the Senate staffers parsed those millions of CIA documents to shatter the agency’s myth of derring-do infallibility and expose the bumbling mismanagement of its two main missions in the War on Terror: incarceration and intelligence. Every profession has its B-team, every bureaucracy has its bumblers. Instead of sending James Bond, Langley dispatched Mr. Bean and Maxwell Smart—in the persons of psychologists James Mitchell and Bruce Jessen. In perhaps its single most damning detail, the Senate report revealed that the CIA paid these two Air Force retirees $81 million to create sophisticated “enhanced interrogation techniques” after they had spent their careers doing little more than administering the SERE torture-resistance curriculum—a mundane job tailor-made for the mediocrities of modern psychology (more on this in a moment).

Case of Abu Zubaydah For all its many strengths, the Senate report is not without some serious limitations. Mired in detail and muffled by opaque pseudonyms, the committee’s analysis of this rich detail is often cursory or convoluted, obscuring its import for even the most discerning reader. This limitation is most apparent in the report’s close case study of Abu Zubaydah, the high-value detainee whose torture at a Thai black site in 2002 proved seminal, convincing the CIA that its enhanced techniques worked and giving these psychologists control over the agency’s program for the next six years. But, says the Senate report, earlier non-coercive interrogation produced more numerous intelligence reports.

This finding is good as far as it goes, but let’s see what more extensive analysis might extract from this critical section of the Senate’s report. Among the countless thousands of interrogations during the War on Terror, Abu Zubaydah’s has been cited repeatedly by conservatives to defend the CIA’s methods.In memoirs published on the tenth anniversary of 9/11, Dick Cheney claimed the CIA’s methods turned this hardened terrorist into a “fount of information” and thus saved “thousands of lives.” But just two week later, Ali Soufan, a former FBI counter-terror agent fluent in Arabic, published his own book claiming he gained “important actionable intelligence” by using empathetic methods to interrogate Abu Zubaydah.

If we juxtapose the many CIA-censored pages of Ali Soufan’s memoir with his earlier, unexpurgated congressional testimony, this interrogation becomes an extraordinary four-stage scientific experiment testing the effectiveness of CIA coercion versus the FBI’s empathy.

Stage One. As soon as Abu Zubaydah was captured in 2002, Ali Soufan flew to Bangkok where he built rapport in Arabic to gain the first intelligence about “the role of KSM [Khalid Sheikh Mohammed] as the mastermind of the 9/11 attacks.” Angered by the FBI’s success, CIA director George Tenet pounded the table and dispatched psychologist James Mitchell, who stripped Zubaydah naked and subjected him to “low-level sleep deprivation.”

Stage Two. After the CIA’s harsh methods got “no information,” the FBI men resumed their empathic questioning of Abu Zubaydah to learn “the details of Jose Padilla, the so-called ‘dirty bomber.'” Then the CIA team took over and moved up the coercive continuum to loud noise, temperature manipulation, and forty-eight hours of sleep deprivation.

Stage Three. But this tough CIA approach again failed, so, for a third time, the FBI men were brought back, using empathetic techniques that produced more details of the Padilla bomb plot.

Stage Four. When the CIA ratcheted up the abuse to confinement that was clearly torture, the FBI ordered Ali Soufan home. With the CIA in sole control, Abu Zubaydah was subjected to weeks of sleep deprivation, sensory disorientation , nudity, and waterboarding but gave no further information. Yet in a stunning bit of illogic, Mitchell claimed this negative result was, in fact, positive since these enhanced techniques showed that the subject had no more secrets to hide. Amazingly, the CIA bought this bit of flim-flam.

Examined closely, the results of this ad hoc experiment were blindingly clear: FBI empathy was effective, while CIA coercion proved consistently counterproductive. But this fundamental yet fragile truth has been obscured by CIA claims of good intelligence from the torture of Abu Zubaydah and by censorship of 181 pages in Ali Soufan’s memoir that reduced his account to a maze of blackened lines that no regular reader can understand.

Unanswered Question More broadly, the Senate committee’s report also fails to ask or answer a critical question: If the intelligence yield from torture was so consistently low, why was the CIA so determined to persist in these brutal but unproductive practices for so long? Among the many possibilities the Senate failed to explore is a default bureaucratic response by a security agency flailing about in fear when confronted with an unknown threat. “When feelings of insecurity develop within those holding power,” reported a CIA analysis of the Cold War Kremlin applicable to the post-9/11 White House, “they become increasingly suspicious and put great pressures upon the secret police to obtain arrests and confessions. At such times police officials are inclined to condone anything which produces a speedy ‘confession,’ and brutality may become widespread.”

Moreover, the Senate’s rigorously pseudonymous format strips its report of an element critical to any historical narrative, the actor, thereby rendering much of its text incomprehensible. Understanding the power of narrative, the CIA has given us the Oscar-winning feature film Zero Dark 30 about an heroic female operative whose single-minded pursuit of the facts, through the most brutal of tortures, led the Navy SEALs to Osama Bin Laden. While the CIA has destroyed videotapes of these interrogations and censored Ali Soufan’s critical account, scriptwriter Mark Boal was given liberal access to classified sources.

Instead of a photogenic leading lady, the Senate report offers only opaque snippets about an anonymous female analyst who played a pivotal role in one of the CIA’s biggest blunders—snatching an innocent German national, Khaled el-Masri, and subjecting him to four months of abuse in the Salt Pit prison. That same operative later defended torture by telling the CIA’s own Inspector General that the waterboarding of Khalid Sheikh Mohammed had extracted the name of terrorist Majid Khan—when, in fact, Khan was already in CIA custody. Hinting at something badly wrong inside the agency, the author of these derelictions was rewarded with a high post in the CIA’s Counter-Terrorism Center.

By quickly filling in the blanks, journalists have shown us the real story about this operative that the Senate suppressed and Hollywood glorified. This CIA “Torture Queen,” reports Jane Mayer in the December 18 issue of the New Yorker, “dropped the ball when the C.I.A. was given information that might very well have prevented the 9/11 attacks; …gleefully participated in torture sessions afterward; …misinterpreted intelligence in such a way that it sent the C.I.A. on an absurd chase for Al Qaeda sleeper cells in Montana. And then she falsely told congressional overseers that the torture worked.”

After all that, this agent, whom Glenn Greenwald has identified as Alfreda Bikowsky, has now been promoted to a top CIA post and rewarded with a high salary that, says an activist website, recently allowed her to buy a luxury home in Reston, Virginia for $875,000. In short, adding the name and narrative reveals a consistent pattern of CIA incompetence, the corrupting influence of intelligence gleaned from torture, and the agency’s perpetrators as self-aggrandizing incompetents.

Cold War History The Senate report’s signal failing is its cursory treatment of the sixty-year history of secrecy that inscribed tolerance for psychological torture into the country’s intelligence community, political culture, and federal laws.

Cold War History The Senate report’s signal failing is its cursory treatment of the sixty-year history of secrecy that inscribed tolerance for psychological torture into the country’s intelligence community, political culture, and federal laws.

Viewed historically, the current controversy is the product of a deeply contradictory U.S. policy toward torture since the start of the Cold War. Publicly, Washington advocated a strong standard for human rights–manifest in the UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights of 1948 and the Geneva Conventions of 1949. Simultaneously and secretly, however, the CIA was developing ingenious new torture techniques in contravention of these same international conventions.

From 1950 to 1962, the CIA led a secret allied research effort to crack the code of human consciousness, a veritable Manhattan project of the mind. While its exotic experiments with LSD led nowhere, CIA-funded behavioral research produced two key findings—sensory deprivation and self-inflicted pain—that became central to its new doctrine of psychological torture.

After four years of mind control research for use against the enemy, President Eisenhower ordered, in 1955, that all American soldiers at risk of capture be trained to resist torture. During the Korean War, about thirty captured US airmen were tortured to make false statements, some on Radio Beijing, that America had used biological weapons in North Korea. Consequently, the Air Force flipped these methods from offense to defense to give its pilots so-called SERE training—an acronym for Survival, Evasion, Resistance, Escape.

After a decade of mind-control research, in 1963 the CIA codified its findings in a secret handbook, cited in the current Senate report, called the “KUBARK Counterintelligence Interrogation” manual with a new method of psychological torture that was, for the next thirty years, disseminated worldwide and within the U.S. intelligence community.

But as the Cold War wound down, Washington abandoned its torture techniques. After a death in custody, the CIA purged these coercive techniques from its interrogation canon and even concluded they were counterproductive. After decades of training Latin American militaries in torture, the Defense Department, under Secretary Dick Cheney, recalled all copies of extant manuals that detailed these illegal methods.

Twelve years later when the Bush administration opted for torture after 9/11, the sole institutional memory for these psychological methods lay in the military’s SERE training. Under contract with the CIA, the two psychologists, Mitchell and Jessen, reverse-engineered this defensive doctrine to produce the agency’s signature “enhanced interrogation techniques.”

Instead of outsourcing torture to allies as Washington had done during the Cold War, Bush’s policies required that CIA agents dirty their own hands with the tortures detailed in the Senate report—both the harsh physical methods (wall slamming, facial grab, stomach slap, rectal feeding), and psychological techniques dating back to the KUBARK manual (sleep deprivation, sensory disorientation, shackling for enforced standing).

Legal Protection for Torture Not only is the use of psychological torture embedded in the nation’s security agencies, it has been sanctioned by U.S. laws designed to prohibit this abuse. The reason for this contradiction is, once again, found in a troubled history ignored by the Senate report.

When the Cold War came to a close, Washington finally ratified the UN Convention Against Torture that banned the infliction of both psychological and physical pain. On the surface, the United States had apparently resolved the long-standing contradiction between its anti-torture principles and its torture practices.

But when President Clinton sent this UN Convention to Congress for ratification in 1994, he included language drafted six years earlier by the Reagan administration with four detailed diplomatic “reservations” focused on just one word in the treaty’s twenty-six printed pages: “mental.”

Instead of the UN Convention’s broad ban on “severe pain or suffering,” these U.S. reservations redefined psychological torture as “prolonged mental harm.” Since “prolonged” was vague (how long is prolonged?) and “harm” was ambiguous (what constitutes harm?), these reservations created enormous loopholes—just like the one Bush lawyers later opened by allowing harm up to “organ failure.”

This language and its loopholes have been repeated, verbatim down to the semicolons, in every U.S. law enacted to comply with the UN Convention—first in Section 2340 of the Federal Code; next in the War Crimes Act of 1996; and most recently in the Military Commissions Act of 2006.

Impunity in America As America now concludes a decade-long debate over impunity, the Senate report serves as a powerful corrective to years of CIA disinformation. Since CBS Television released those photos from Abu Ghraib prison back in 2004, the United States has been moving, almost imperceptibly, through a five-step process of impunity over torture quite similar to those experienced earlier by nations such as England, France, or the Philippines.

Step One—Bad Apples. For a year after the Abu Ghraib exposé, Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld blamed some bad apples by claiming the abuse was “perpetrated “by a small number of U.S. military.”

Step Two— National Security. In the months following Obama’s inauguration, Republicans took us deep into the second stage by invoking national security, with Dick Cheney saying repeatedly the CIA’s methods “prevented the violent deaths of thousands, perhaps hundreds of thousands, of people.”

Step Three—Unity. In April 2009, President Obama brought us to the third stage of impunity when he visited CIA headquarters and appealed for national unity, saying : “We’ve made some mistakes,” but it’s time to “acknowledge them and then move forward.”

Step Four—Exoneration.After the assassination of Osama bin Laden in May 2011, neo-conservatives formed an a cappella media chorus to claim, without any factual basis, that torture led us to Bin Laden. Within weeks, Attorney General Eric Holder ended the investigation of alleged CIA abuse without a criminal indictment, exonerating both the interrogators and their superiors.

Step Five—Vindication.Since the tenth anniversary of 9/11 in September 2011, we have entered the fifth, final, and most fraught step toward impunity: vindication before the bar of History. Until now, the CIA’s defenders were winning this political battle—interrogation videos destroyed, books censored, indictments quashed, lawsuits dismissed, imagined intelligence coups celebrated, medals awarded, bonuses paid, and promotions secured.

But with the release of this Senate report and the media’s pursuit of the facts behind its obfuscations, the full story of abuse, fabrication, and dissimulation inside the CIA is finally starting to emerge. Instead of steely guardians willing to break laws, trample treaties, and dedicate their lives in defense of America, this report reveals these perpetrators as mendacious careerists willing to twist any truth to win a promotion or secure a lucrative contract.

Conclusion Despite its rich fund of hard-won detail, the Senate report has, at best, produced a neutral outcome, a draw in this political contest over impunity. Over the past forty years, there have been a half-dozen similar scandals over torture that have followed a familiar cycle—revelation, momentary sensation, vigorous rebuttal, and then oblivion. Unless we inscribe the lessons from this Senate report deeply into the country’s collective memory, then some future crisis might prompt another recourse to torture that will do even more damage to this country’s moral leadership.

See more at: http://historynewsnetwork.org/article/157950#sthash.QzcOAFKd.dpuf

Also by Alfred McCoy, from the University of Wisconsin Press:  POLICING AMERICA’S EMPIRE: The United States, the Philippines, and the Rise of the Surveillance State.

POLICING AMERICA’S EMPIRE: The United States, the Philippines, and the Rise of the Surveillance State.

POLICING AMERICA’S EMPIRE: The United States, the Philippines, and the Rise of the Surveillance State

POLICING AMERICA’S EMPIRE: The United States, the Philippines, and the Rise of the Surveillance State