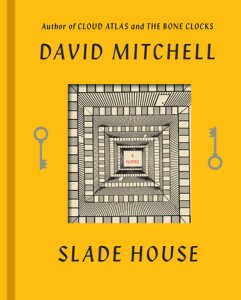

A new novel from David Mitchell, Slade House, was published in October 2015. Following up on a 2015 special issue of the journal SubStance devoted to Mitchell’s extraordinary works of fiction, Paul Harris and Patrick O’Donnell previewed Slade House in a pre-publication discussion. Now that the novel has received its early critical response, Harris and O’Donnell review the reviews.

Paul Harris

PAUL HARRIS: As we suspected, the reviews of David Mitchell’s Slade House seem quite cleanly divided between two types of responses. Either the novel is a “devilishly fun … fiendish delight” fit to devour in a single sitting like the twins sucking down another soul, or it is dismissed as “soul-sucking mumbo-jumbo” registering too high on the “wackometer” to enjoy, let alone take seriously.

The most positive reviews see it as an entertainment given substance by the “human warmth” of its characters or the philosophical questions it raises: John Boyne calls it “a highly effective, creepy and witty ghost story, designed to unsettle the reader and raise questions about what all of us might do in our quest for immortality.” The most negative assessments see Slade House as a letdown, or even a betrayal: for Scarlet Thomas, the novel moves Mitchell from exemplary author (“what would David Mitchell do?”) to one “writing [his] own fan fiction.” Thomas criticizes Mitchell for moral and political disingenuousness: the novel sounds “hefty themes” but transfers “meaning and purpose” from the real to the “supernatural” and ends up offering only a “Bill and Ted philosophy” that we should all “be excellent to one another.”

Patrick, do you see a third alternative to these views, an excluded middle that gets us out of the muddle of either seeing Slade House as a lite fictional funhouse or a shrill failure without much value? In considering this question myself, one avenue that I’ve thought about is genre. Reflecting on the many reviews I read, I realize how critical the lens of genre is in the reader’s reception of Slade House. The novel has garnered ubiquitous comparisons to Henry James’s Turn of the Screw for giving the ghost story a new twist, while also being lauded for its Lovecraftian integration of horror and science fiction. Others, though, diagnose Slade House as over the top in its deployment of genre(s) and heavy-handed in explaining or laying bare the rules of its fictive world. I found science fiction writer and critic Paul Kincaid’s review the most informed, persuasive take on this issue. Though the novel as a whole sounds the horror note, Kincaid points out that in each section Mitchell “sets up genre expectations and then upends them in a very deliberate and calculated way.” This pattern is what makes Mitchell so successful: Kincaid concludes that Slade House “works, as all of Mitchell’s novels have worked, because we start out reading one thing and end up reading something very different indeed.”

Mitchell both explodes the boundaries of genre (by refusing to stay within the confines of distinct classes of fiction) and implodes them (by miming a genre and then turning it inside out).

Kincaid’s review made me appreciate Mitchell’s constant upending of expectations, but it also made me wonder whether the game can reach a point of exhaustion. Mitchell’s fictional arcs can abruptly shift dimensions, it seems, because it is all fiction—it’s all made up, so you are free to make anything up and keep changing the rules; once this is the case, ultimately there is nothing that can be trusted and nothing that cannot be done.

Slade House seems to assert this view of narration or fiction most explicitly or literally. The twins have infinite fiction-creating power dressed up in Lacuna-Operandi-Orison stagesets, but they SO free to compose the scene and inhabit characters that there are no rules left. Behind the world being constructed is an omnipotent wizard who can wave a wand at any time, without any need to justify matters. The orison of the Fox and Hounds pub featuring Jonah commandeering Fred Pink in the novel’s penultimate section felt the most contrived; the sudden shift left me more ticked off than tickled. This reversal then sets up the final turning of the tables, at yet another level of abstraction, when Marinus’s powers prove even more infinite than the Grayers, and time enters the Lacuna. As readers, we should be able to see this coming because that final section is narrated by Norah, and each section has shown the destruction of unsuspecting narrators who think they are in one world with one set of rules but turn out not to know who or what they are up against.

Returning to one strand of our previous discussion, I am left wondering what Slade House tells us about the house of fiction. If the rules of conjuring have no rules, or all genres and conventions can be flouted at any time, then there is not enough suspense or tension left to warrant our entering into a state of suspended disbelief—put differently, with nothing to believe in, there is nothing not to believe in, and hence no disbelief either.

What are your thoughts about this very basic but also encompassing question of the rules for constructing houses of fiction?

Patrick O’Donnell

PATRICK O’DONNELL: Like you, I am not terribly surprised by the bifurcated responses from the reviewers, though I think those that regard Slade House as a minor entertainment really miss the mark. Many of the responses that you cite proceed from a set of expectations regarding both David Mitchell (a major novelist in mid-career) and the fictional genres that he characteristically engages—or rather, the fictional sub-genres (as they are often viewed) of fantasy, science fiction, horror. The combination of “major novelist” and “sub-genre” poses a dilemma for reviewers who have a hard time putting together the notions of serious literature and popular genres, despite much important Anglo-American fiction since the 1960s closing the gap between “high” and “low” art.”

I’ll simply note in this regard that one of Mitchell’s fictional mentors, Haruki Murakami, received a similar set of binary responses to 1Q84. Reviewers, in the main, weren’t particularly happy with that novel’s engagement with what they perceived as a chaotic mix of realism, mysticism, fantasy, and various shaggy dog pyrotechnics.

There seems to be an equal amount of difficulty with the expectation that each succeeding novel by an acknowledged, important novelist and prolific writer must somehow “top” everything that has come before, or offer some kind of visible, steady advance (“the best David Mitchell novel yet!”) in an ever-rising career trajectory.

I’m quite sure there is a large excluded middle between viewing Slade House as either a delightful (but minor) entertainment or a “fan fiction.” There are many ways seeing the novel that do not rely so much on the expectations I’ve mentioned.

I’m in complete agreement with you that examining what Mitchell is do ing with genre in Slade House, and throughout his fiction, offers one way of getting at what is at stake in this newest work. Some of the reviewers seem to suggest that nothing important is at stake, particularly those who are disappointed that Mitchell seems to be trading off his investment in the “big themes” of human greed, exploitation, colonialism, mortality, historical inevitability, or historical change, etc., for sheer fun, fantasy, and entertainment (or lack thereof). And, I think you are quite right in suggesting that the novel is constantly turning the tables on itself and on the expectations of its readers by positing that its own fictional rules are constantly changing and subverting their own tenancy. I’m reminded of the line in John Barth’s Lost in the Funhouse: “for whom is the funhouse fun?”

ing with genre in Slade House, and throughout his fiction, offers one way of getting at what is at stake in this newest work. Some of the reviewers seem to suggest that nothing important is at stake, particularly those who are disappointed that Mitchell seems to be trading off his investment in the “big themes” of human greed, exploitation, colonialism, mortality, historical inevitability, or historical change, etc., for sheer fun, fantasy, and entertainment (or lack thereof). And, I think you are quite right in suggesting that the novel is constantly turning the tables on itself and on the expectations of its readers by positing that its own fictional rules are constantly changing and subverting their own tenancy. I’m reminded of the line in John Barth’s Lost in the Funhouse: “for whom is the funhouse fun?”

For you, it seems that the suspension of belief in the rules that undergird the suspension of disbelief results in a kind of mise en abyme of infinite play and a loss of semiotic power that, for those unhappy with certain putative versions of postmodernism, signals a dead end of sorts.

I’d like to pose another possible way of seeing all of this. The novel—quite seriously, I think, for all of its esoteric claptrap, as well as its fractality and generic hybridity—poses the questions of who is making the rules, and what are the hidden or manifest agendas of their making?

How do those in power (the rule-makers) stay in power, and what do power-mongering and rule-making—which in Mitchell’s fiction has everything to do with the enforcement and construction of a supposedly orderly and stable “reality” that enables those in power to remain empowered—have to do with our sense of what constitutes human identity?

Michel Foucault has performed for us the crucial work of explaining how power operates in relation to knowledge: he poses and answers a series of complicated epistemological questions. But he doesn’t get at what power has to do with us ontologically, and I think that is what Mitchell is trying to get at in his work, including Slade House, with its soulsucking semi-immortals and its rebirthed “saviors” like Marinus, who operates not as a deus ex machina but as a last-ditch interventionist embodying the unforeseen good luck of those who will not be destroyed by the Grayers in the future (though that’s not to say something else won’t come along to take their place). The novel might then be seen as extending the fantasy of empowerment, perhaps to its absurdist limit, enabling us to ask some key questions: what happens if everyone is in on the lie of this fantasy that disguises the real fragility and vulnerability of the empowered? What happens if we see that power, with all of its seductions, is the opposite of what constitutes (or should constitute) life and being? What if the construction of reality is put into the hands of the multitude and not the hands of the one per cent?

Let me put the ball back in your court, Paul: How do you see Slade House in relation to Mitchell’s previous fiction: as an advance, an extension, a repetition, a refutation—or, if none of those, how can we regard it? Is there any way to tell where Mitchell goes from here?

PAUL HARRIS: Pat, you just hit the refresh button on Slade House for me: I look forward to rereading it to watch how empowerment is linked to world-making and see how it plays in these terms. You’re right to remind Mitchell readers that, just as he collapses serious and popular genres, he also sounds heavy themes in seemingly light stories.

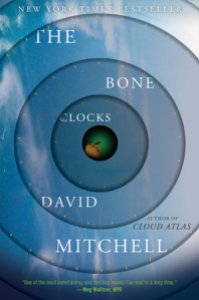

As for how Slade House relates to Mitchell’s previous work, in form and structure it most clearly resembles Ghostwritten, Cloud Atlas, and Bone Clocks. All these texts are divided into discrete sections with different narrators set in different decades/centuries. The obvious difference is that Slade House takes place at one setting, while the episodes in the other novels span the globe. Just as the spatial setting doesn’t change, Slade House also generates a more static image or concept of time than those other novels. Even though its episodes move forward nine years each time, each plays out the same scenario, so there is not the same kind of plot advancement as in the other texts.

The game afoot is to defy mortality: the Grayers persist in a Lacuna where time doesn’t pass, and they consume engifted souls to keep themselves from aging. The narrative time thus progresses in a recursive loop; each nine years a new narrator enters a new Orison, but the modus operandi remains the same. The novel’s temporality reminds me a bit of a video game, where a new player enters and tries to beat the villains. It is reminiscent of the film Run Lola Run (explicitly framed as a video game sequence, run three times through), except that not all characters remain the same through the iterations of the game-time. As in that film, here there is  learning, or shared information, that accumulates in the game’s iterations: knowledge and weapons are passed forward. For the reader, each section makes us increasingly familiar with the plot routine (enter the house, consume Banjanx, go upstairs, soul is consumed). So, as we make our way through it, the novel seems to become more and more suspended in the ghostly time of its fictional house. Of course, like all Mitchell novels, it ends with a new beginning. Instead of Norah’s death closing the deal, she transverses into a fetus and vows revenge on Marinus—and surely we can anticipate seeing this confrontation in a future novel.

learning, or shared information, that accumulates in the game’s iterations: knowledge and weapons are passed forward. For the reader, each section makes us increasingly familiar with the plot routine (enter the house, consume Banjanx, go upstairs, soul is consumed). So, as we make our way through it, the novel seems to become more and more suspended in the ghostly time of its fictional house. Of course, like all Mitchell novels, it ends with a new beginning. Instead of Norah’s death closing the deal, she transverses into a fetus and vows revenge on Marinus—and surely we can anticipate seeing this confrontation in a future novel.

This brings me to the other question you posed: what direction Mitchell might take from here. Mitchell is particularly fun to play this game with, because he keeps defying expectations and exploring new territories. In imagining Mitchell’s career trajectory, I don’t think about his work as a single arc or linear process. I’ve written before that it seems more fitting to imagine his texts as iterations in a fractal imagination. The recurring characters, themes, and genres prompt me to picture his “übernovel” as a sort of strange attractor; each text marks a recursive movement—both returning to familiar sites and opening new terrains—that simultaneously fleshes out and fills in more and more of his fictional universe. With each textual iteration, the overall shape and contours of his übernovel become increasingly clear and its constituent parts more densely interwoven.

If we conceptualize Mitchell’s work this way, then speculating where Mitchell’s work will go next would entail running the strange attractor simulation through its next iteration. Stanislaw Lem actually thought about authors’ work in this way in his br illiant “History of Bitic Literature” thought-experimental essay published in 1973. (Lem is a “Prescient” if ever there was one!) Lem imagines computing machines capable of “bitic mimesis,” machine-written imitation of writers. He describes a novel by Pseudodostoevsky, created by a computer processing all existing Dostoevsky novels as information in “the space of meanings” and modeling his corpus as “a curved mass, recalling in its structure an open torus, that is, a ‘broken ring’ (with a gap). Thus it was a relatively simple task (for machines, of course, not for people!) to close that gap, inserting the missing link” (58).

illiant “History of Bitic Literature” thought-experimental essay published in 1973. (Lem is a “Prescient” if ever there was one!) Lem imagines computing machines capable of “bitic mimesis,” machine-written imitation of writers. He describes a novel by Pseudodostoevsky, created by a computer processing all existing Dostoevsky novels as information in “the space of meanings” and modeling his corpus as “a curved mass, recalling in its structure an open torus, that is, a ‘broken ring’ (with a gap). Thus it was a relatively simple task (for machines, of course, not for people!) to close that gap, inserting the missing link” (58).

At first sight, it seems much harder to model Mitchell’s writing in that way than Dostoevsky’s; the latter seems to have an internal stylistic and generic consistency that Mitchell purposely eschews. But with each successive novel, his corpus seems to gain coherence and consistency, assuming some sort of discernible shape. If I tried to model Mitchell’s work, I wouldn’t start from “the space of meanings” in the words, but rather I would list a set of recurring elements—island or city settings, cats, types of characters (angry writer, gifted rebellious teen)—and a template for form, such as every ending a beginning, stand-alone episodic stories serving a larger plot, etc.

Putting aside this digressive line of speculative unreasoning, one could make a more educated guess at predicting the shape of Mitchell’s future work by following the clues he himself has laid down. In her excellent piece about The Bone Clocks, Kathryn Schulz reports that Mitchell mapped out his next several several texts: “These include further adventures with soul-eating villains, a trio of linked novellas set in New York in the late ’60s and early ’70s, a return to historical fiction (different hemisphere this time), and a fictionalized biography of an 18th-century person you’ve probably heard of. The final installment of the Marinus trilogy will follow all that. Mitchell is also toying with an idea for what will by then be his 12th novel. It is set 250 million years in the future.” It will be interesting to see if Mitchell adheres to this plan or if he cannot stop his restless imagination from going in other directions. Regardless of what Orisons Mitchell sends from his Operandi though, I confess that I’ll always eagerly eat the Banjanx he serves up, as long as my psychovoltage holds out.

I have suggested that Mitchell might serve readers well by publishing serially rather than in novels. Wouldn’t it be great if we could ‘subscribe’ to him, and receive his novels in installments, rather than waiting for the whole work to be done and consuming it all at once? This would make reading Mitchell much more fun; not only would we endure shorter breaks between new Mitchell texts, but we would also stay in suspense much longer when one section ends, and have time to wonder what is coming next. This would also prevent book reviews from spoiling the surprise of reading his novels, the problem we attempted to mitigate in our first exchange.

I find reading his books now comparable to binge-watching seasons of a TV series. Just playing with this scenario, if the storylines of several novels are already set, one could even imagine a point where Mitchell could hire ‘writers’ to execute textual episodes in the ongoing übernovel saga. This turnabout on himself would even be fair play in some way. Mitchell has been a kind of authorial noncorporum who infiltrates the minds of narrators, styles of authors, and conventions of genres, and speaks through them. He does more than allude to other writers; it is like he dons their modus operandi and produces a new version of them: number9dream is like Murakami as done by Mitchell; Cloud Atlas is like Mitchell does Defoe, Melville, Nabokov, Hoban, etc. So why not see if talented writers could ‘do’ Mitchell?

David Mitchell

Of course, I don’t imagine or expect that Mitchell would ever outsource his stories to other writers. But I do think that he and his editor/publisher/agent might consider alternative delivery systems beyond print novels. He has already migrated into twitter; why not break new ground in publishing fiction? I actually suggested this to Mitchell a year ago; he simply responded in conventional terms, saying that he would continue to follow the existing process. This occurred at a book tour stop for Bone Clocks, so maybe it wasn’t the right context for him to consider other options.

So, I’ll bounce it back to you—where do you see Mitchell going from here, and what do you think of his moving to some sort of serial publication, adapted to the contemporary historical context?

PATRICK O’DONNELL: Thanks, Paul, for this lively speculation on where Mitchell might go from here. I completely agree that his fictions, as they unfold across the time of their writing, are “iterations in a fractal imagination”—that’s a terrific way of viewing his work incrementally. Doing so, as you suggest, leads to many interesting possibilities for reading him in the future (as well as considering what his writing in/of the future might look like).

There are “personalities” like Marinus to consider, who appears to be an amalgamation of tendencies or projections, a wavering needle on the scale that runs from protagonist to antagonist. Then there are all the atomistic shapes and designs of Mitchell’s work, taken fractally as a non-totalizable totality—rooms, islands, fortresses, cities, avenues, pathways, landscapes, artifacts, assemblages of all kinds. One finds all of these and more in any novelist of Mitchell’s encyclopedic demeanor, but in observing these iterations across—now—seven novels, we definitely get the sense that each of these shapes and designs bear striking similarities but are radically different from novel to novel.

One of the pleasures taken by many of Mitchell’s fans is playing “Where’s Waldo?” with his novels as they appear, focusing on the transmigratory characters of the novels. It’s rather like spotting the various manifestations of Tom Hanks in the film adaptation of Cloud Atlas (which, by the way, despite some dismal reviews, provides to my mind a compelling and precise visual rendering of Mitchell’s sense that civilizations across time are made up of transmutable identities, forms, and objects in continuous collision with each other). But to play “Where’s Waldo?” with the novels largely misses the point, because doing so overdetermines character as the primary element of his fiction.

I know there are some who read the repeated/rebirthed characters of Mitchell’s novels as generating some concept of transcendent human identity, or as a comment about the survival of “the human” over the reaches of time and amidst the collapse of civilizations and cultures, but I don’t quite see it that way. The repeated identities of his novels, to me, are simply one set of elements among many that circulate molecularly through his fiction: his game is terrain, not identity, and thus he is always moving—at times sequentially, at times randomly—between generated worlds always in the process of formation. This is another reason why I think the Wachowskis/Twyker adaptation of Cloud Atlas was so successful while being true to its materiality as a visual experience: while probably difficult to understand “thematically,” especially for those not familiar with the novel and thus challenged to follow the intertwined plots of the film, visually, it captured perfectly Mitchell’s sense that history “happens” in a fragmented, non-linear fashion, that cultures and identities evolve fractally, and that the “whole” of reality is an illusion for which we generate partial narrative patterns and signifying chains as compensations.

David Mitchell

Given all of that, I agree entirely that the future “Mitchell” may well try out different forms and kinds of writing made available as the digital age progresses. As we know, writing and thinking are being radically transformed by the advent of social media, and there are several contemporary writers beginning to experiment with those forms in interesting ways.

The origins of Slade House in Twitter certainly indicates that Mitchell may well be moving into this territory. It will be interesting to see what happens along these lines given that, predictably, he will continue to be strongly tied to the notion of the book and the narrative traditions that have emerged in the post-Gutenberg book culture. (For many, “the book” is done, though not, I think, for David Mitchell.) As you suggest, Mitchell may well move into a form of serial publication that somehow replicates both the novel’s traditional seriality (think of the apocryphal crowds waiting on the Brooklyn docks for the arrival of the latest number of The Old Curiosity Shop in the nineteenth century, and yielding up a universal moan when readers collectively came upon the death of Little Nell) and the new serialities of the digital age: semirandom, occasional, serendipitous, wherever Google takes us.

But I think as well that Mitchell may in the future be exploring both other media and new ways of viewing how human cognition and behavior work, made available by the fast-moving advances in neuroscience and genetics currently taking place. The two indicators of this for me are his recent collaborative work with his wife, KA Yoshida, on the English translation of Naoki Higashida’s The Reason I Jump, and the “3-D film-opera,” The Sunken Garden, with Michel van der Aa. I think it’s quite possible that Mitchell will be engaging in future collaborative projects that mix media (as he does genres in his novels) or that involve collaborative writing projects of some kind.

David Mitchell and Michael van der Aa

And—given Mitchell’s fascination with childhood and adolescence (revealed most fully in blackswangreen but visible throughout his fiction), combined with the cognitive and learning processes of children that he directly engages with personally and in the act of co-translating the memoir of an autistic teenager—I would not be at all surprised to see Mitchell writing young adult fiction, or, in another dimension, exploring the ways in which narrative operates cognitively for different minds. In this, as in all of his work, I believe his focus will be not upon the universal, but upon the differences, the fractures in the surface and the gradations in the terrain, however we stumble upon them.

PAUL HARRIS: Patrick, this has been a great pleasure. Thank you for contributing your perspectives on David Mitchell to SubStance. I look forward to reading more of your work and perhaps resuming this conversation when “Season 8” of Mitchell’s übernovel comes out.

Paul Harris

Paul A. Harris is a co-editor of SubStance and a professor of English at Loyola Marymount University. He served as president of the International Society for the Study of Time from 2004-2013 and edited the recent SubStance issue David Mitchell in the Labyrinth of Time. His current project is The Petriverse of Pierre Jardin.

Patrick O’Donnell

Patrick O’Donnell is a professor of twentieth- and twenty-first-century British and American literature at Michigan State University; he is the author and editor of over a dozen books on modern and contemporary fiction, most recently, The American Novel Now: Reading American Fiction Since 1980 (Wiley-Blackwell, 2010), and A Temporary Future: The Fiction of David Mitchell (Bloomsbury, 2015). He is currently working on a book about Henry James and contemporary cinema.

April 1

April 1

April 26

April 26

She previously won the Brittingham Prize for her collection

She previously won the Brittingham Prize for her collection

defiantly kept his seat and did not join in the applause.

defiantly kept his seat and did not join in the applause.

ing with genre in Slade House, and throughout his fiction, offers one way of getting at what is at stake in this newest work. Some of the reviewers seem to suggest that nothing important is at stake, particularly those who are disappointed that Mitchell seems to be trading off his investment in the “big themes” of human greed, exploitation, colonialism, mortality, historical inevitability, or historical change, etc., for sheer fun, fantasy, and entertainment (or lack thereof). And, I think you are quite right in suggesting that the novel is constantly turning the tables on itself and on the expectations of its readers by positing that its own fictional rules are constantly changing and subverting their own tenancy. I’m reminded of the line in John Barth’s Lost in the Funhouse: “for whom is the funhouse fun?”

ing with genre in Slade House, and throughout his fiction, offers one way of getting at what is at stake in this newest work. Some of the reviewers seem to suggest that nothing important is at stake, particularly those who are disappointed that Mitchell seems to be trading off his investment in the “big themes” of human greed, exploitation, colonialism, mortality, historical inevitability, or historical change, etc., for sheer fun, fantasy, and entertainment (or lack thereof). And, I think you are quite right in suggesting that the novel is constantly turning the tables on itself and on the expectations of its readers by positing that its own fictional rules are constantly changing and subverting their own tenancy. I’m reminded of the line in John Barth’s Lost in the Funhouse: “for whom is the funhouse fun?”

learning, or shared information, that accumulates in the game’s iterations: knowledge and weapons are passed forward. For the reader, each section makes us increasingly familiar with the plot routine (enter the house, consume Banjanx, go upstairs, soul is consumed). So, as we make our way through it, the novel seems to become more and more suspended in the ghostly time of its fictional house. Of course, like all Mitchell novels, it ends with a new beginning. Instead of Norah’s death closing the deal, she transverses into a fetus and vows revenge on Marinus—and surely we can anticipate seeing this confrontation in a future novel.

learning, or shared information, that accumulates in the game’s iterations: knowledge and weapons are passed forward. For the reader, each section makes us increasingly familiar with the plot routine (enter the house, consume Banjanx, go upstairs, soul is consumed). So, as we make our way through it, the novel seems to become more and more suspended in the ghostly time of its fictional house. Of course, like all Mitchell novels, it ends with a new beginning. Instead of Norah’s death closing the deal, she transverses into a fetus and vows revenge on Marinus—and surely we can anticipate seeing this confrontation in a future novel. illiant “History of Bitic Literature” thought-experimental essay published in 1973. (Lem is a “Prescient” if ever there was one!) Lem imagines computing machines capable of “bitic mimesis,” machine-written imitation of writers. He describes a novel by Pseudodostoevsky, created by a computer processing all existing Dostoevsky novels as information in “the space of meanings” and modeling his corpus as “a curved mass, recalling in its structure an open torus, that is, a ‘broken ring’ (with a gap). Thus it was a relatively simple task (for machines, of course, not for people!) to close that gap, inserting the missing link” (58).

illiant “History of Bitic Literature” thought-experimental essay published in 1973. (Lem is a “Prescient” if ever there was one!) Lem imagines computing machines capable of “bitic mimesis,” machine-written imitation of writers. He describes a novel by Pseudodostoevsky, created by a computer processing all existing Dostoevsky novels as information in “the space of meanings” and modeling his corpus as “a curved mass, recalling in its structure an open torus, that is, a ‘broken ring’ (with a gap). Thus it was a relatively simple task (for machines, of course, not for people!) to close that gap, inserting the missing link” (58).

UWP’s production manager for journals, John Ferguson, has given each journal a fresh new cover and interior text design.

UWP’s production manager for journals, John Ferguson, has given each journal a fresh new cover and interior text design. orty other presses are participating in the AAUP’s

orty other presses are participating in the AAUP’s