A Two-Child Limit Imposed on Political Candidates in India—Does It Work?

In India, policy-makers have looked to population control as a means of increasing resources per capita and reducing widespread poverty. Since 1992, eleven Indian states have experimented with restricting elected village council positions to candidates with two or fewer children. The hope is that leaders with small families would inspire their constituents to follow suit. In a new study, researchers S. Anukriti (Boston College) and Abhishek Chakravarty (University of Manchester) found the policy was effective in reducing family sizes, but it worsened the sex ratio as families favored boys.

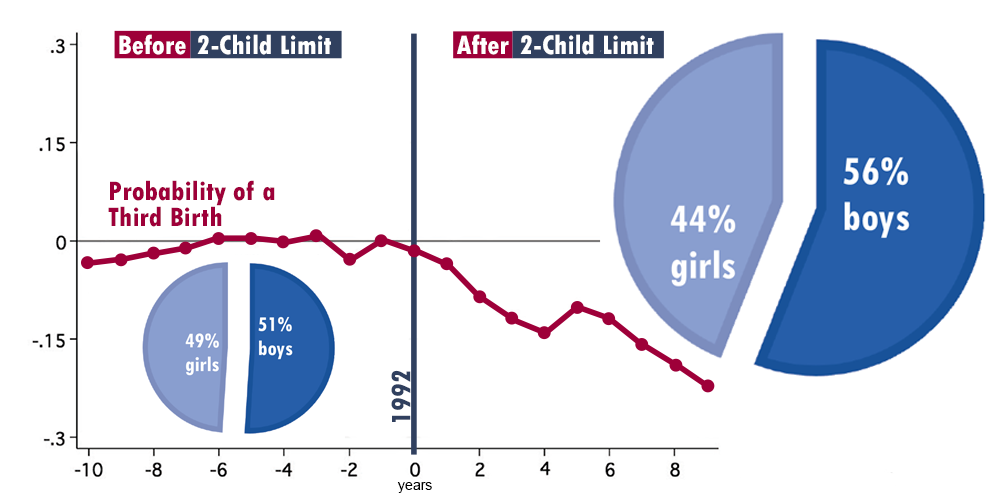

By comparing states that enacted this reform with those that did not, Anukriti and Chakravarty were the first to study whether the general population reduced their fertility in response to the policy. They found that couples with two children were 9 percent less likely to have a third child, and the probability of having three or more children in any given year declined by 4.42 percent after the reform. Infant mortality also declined significantly post-reform in states adopting the policy, suggesting that parents invested more resources per child since they had fewer children.

However, the policy worsened the already male-biased sex ratio by more than 10 percent among second and following births in certain castes. The success of the policy is therefore undermined by increased gender inequality, due to high prevailing son preference in India.

So how can the benefits of the policy be realized without a worsening sex ratio? According to the authors, “Population control initiatives in India need to be combined with educational efforts or incentives that address parents’ preference for boys to mitigate the adverse impacts of declining family size on the sex ratio.”

Read the full study in the Journal of Human Resources: “Democracy and Demography: Societal Effects of Fertility Limits on Local Leaders” by S. Anukriti and Abhishek Chakravarty.