Old-for-Grade vs. Young-for-Grade School Start—What about Siblings?

A major concern of parents of young children is when and to what school they should send their kids. The question of timing has become particularly salient since popular media began reporting on the consequences of school entry policies for student achievement and long-run outcomes. There is ample evidence that old-for-grade children—those that are born right after school entry cutoffs—perform better in elementary and middle school than young-for-grade children. Long-run consequences of school entry policies are less clear and seem to depend on country and institutional context, but there is some evidence that these effects persist into adulthood and affect university enrollment, criminal activity, and wages.

Given the robust evidence on cognitive advantages for old-for-grade children, Karbownik and Özek asked whether these school entry policies can also impact siblings of the children affected by the school entry policy and if so, to what extent.

The authors use detailed individual-level school records from a large, anonymous school district in the state of Florida, which enables linking all public school students to their place of residence, providing information on cognitive ability, household characteristics, and family composition.

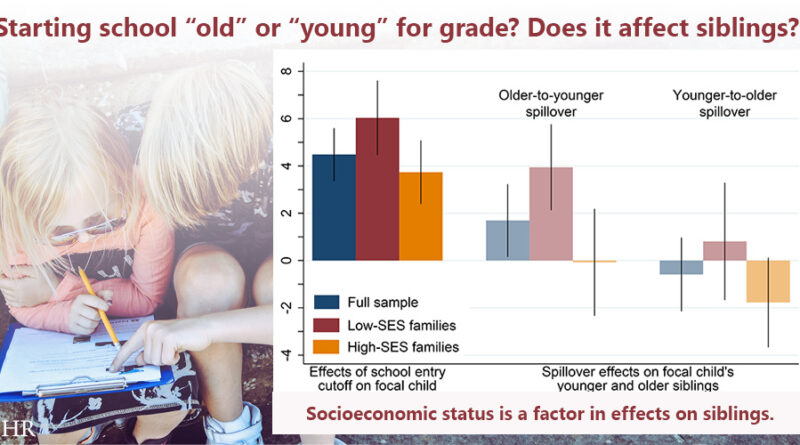

As in many previous studies, Karbownik and Özek first document that students born just after the state’s school entry cutoff significantly outperform those with birthdays just before this cutoff, and they do so by up to 23% of a standard deviation. The team then shows that siblings of those children are likewise affected, but these spillover effects are not uniform.

In particular, they show that the younger siblings of old-for-grade students significantly outperform the younger siblings of comparable young-for-grade students, but this older-to-younger sibling spillover effect only exists in less affluent families. On the other hand, if the younger child is born right after the school entry cutoff, the cognitive advantage has negative effects on the test scores of their older sibling that are only present in relatively affluent families.

What might explain these seemingly contradictory findings? The authors argue that both role-modeling and parental resource allocation could be at play. Regardless of family affluence, it is reasonable to expect the role model effect to be more pronounced in older-to-younger spillovers because older siblings have, on average, greater knowledge and experience than younger siblings. At the same time, parents may invest their resources differentially across their children depending on the signals they receive about the cognitive skills of their child. In particular, they can allocate their resources in a reinforcing fashion (towards the higher-performing sibling) or in a compensatory fashion (towards the lower-performing sibling). It is also reasonable to assume this reallocation channel is more relevant in relatively affluent families.

As such, the authors argue that these findings are consistent with (i) role model effects that are more prominent in the older-to-younger setting and (ii) reinforcing behavior in more affluent households, which could be offsetting the positive role model effect in the older-to-younger setting but leading to negative spillover effects in the younger-to-older setting. One piece of evidence strongly corroborating this interpretation in more affluent households is the fact that in these families the negative effect occurs only after the younger child starts getting tested, revealing their relative cognitive advantage generated by school entry policy to the parents.

The results of this study are critical from a policy perspective. First, they show that commonly used school entry cutoff policies not only have consequences for directly affected children, but can also spill over into other members of the focal child’s family. Thus, the pool of affected children is much larger than initially thought based on prior research. Second, it shows that the same educational policy could generate both positive and negative impacts, depending on the characteristics of the affected household, putting the “one-size fits all” policy approach into question. The take-away? Karbownik and Özek: “Policymakers should be cautious when designing and implementing educational interventions, since their target population could be different from the full population of affected individuals.”

Read the study in the Journal of Human Resources: “Setting a Good Example? Examining Sibling Spillovers in Educational Achievement Using a Regression Discontinuity Design” by Krzysztof Karbownik and Umut Özek.

***

Krzysztof Karbownik (@chriskarbownik) is assistant professor of economics at Emory University. Umut Özek (@uozek) is Principal Economist at the American Institutes for Research.