Disaster Recovery—Who Gets Left Behind?

Major disasters are frequently followed by compensation or aid, but little is known about recovery from such large, but compensated, shocks. Tahir Andrabi, Benjamin Daniels, and Jishnu Das surveyed households four years after the 2005 “great” earthquake in Northern Pakistan, to learn how the earthquake affected families in the long run, after accounting for the effects of aid.

The earthquake was the first of this magnitude to hit the country since 1935. The substantial death and destruction from the earthquake was closely tied to distance from the fault line, but was not correlated with pre-existing village and household characteristics. This pattern allowed the team to compare across households four years after the affected regions were struck—then compensated with significant inflows of aid from multiple sources, including unconditional cash to families.

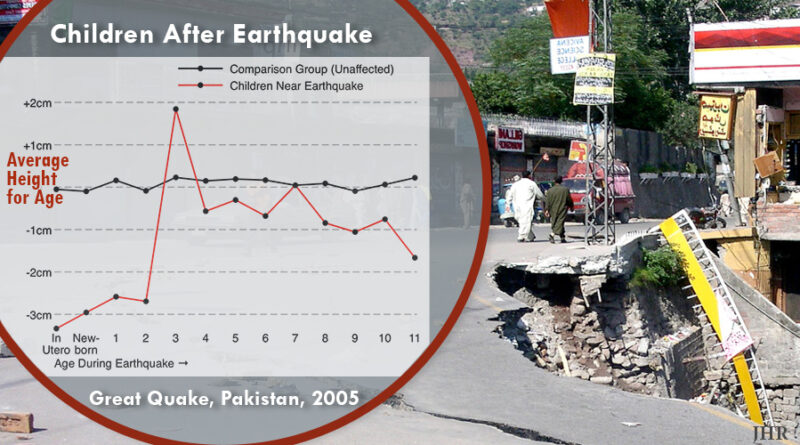

Comparing villages at varying distances from the fault line, the team shows that four years after the earthquake, adult and household outcomes were identical, regardless of earthquake exposure. Despite substantial rebuilding and apparent recovery, large differences had emerged and persisted in children’s health and education outcomes. Children living closer to the fault line who were in utero to age two at the time of the earthquake were significantly shorter in 2009, with no effects among older children.

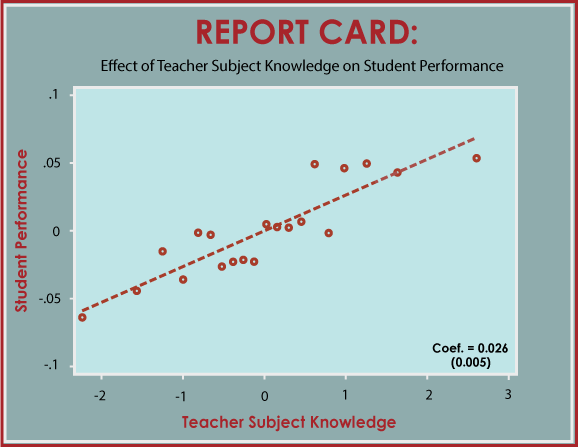

Beyond physical growth, children living close to the fault line who were aged 3–11 during the earthquake showed substantial deficits in test scores (but not school enrollment). Calibrated against annual learning, this amounted to a two-year learning deficit, with similar gaps at all ages. Learning gaps were much larger for children with uneducated mothers, exacerbating existing socioeconomic inequalities in exposed villages. Surprisingly, the learning deficit observed after four years was many times larger than what could be explained by school closures alone. This result led Andrabi, Daniels, and Das to conclude that affected children must have continued falling behind even after returning to school.

So what is the take-away? Das: “These medium-term effects show that even when disasters appear ‘fully compensated,’ protecting children’s well-being and future income requires dedicated support directed to kids.”

Read the study in the Journal of Human Resources: “Human Capital Accumulation and Disasters: Evidence from the Pakistan Earthquake of 2005,” by Tahir Andrabi, Benjamin Daniels, and Jishnu Das.

***

Tahir Andrabi (@AndrabiTahir) is Stedman-Sumner Professor of Economics at Pomona College. Benjamin Daniels (@_bbdaniels) is a gui2de Research Fellow at Georgetown University. Jishnu Das is a professor in the McCourt School of Public Policy and the School of Foreign Service at Georgetown University.