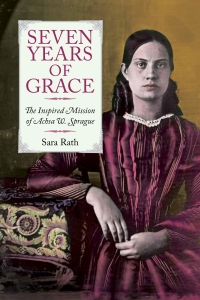

A guest post by Sara Rath. Her new book Seven Years of Grace: The Inspired Mission of Achsa W. Sprague is published by the Vermont Historical Society. (It is distributed by the University of Wisconsin Press.)

When you write someone’s biography, it’s like assembling a puzzle. But if that person lived in the mid-nineteenth century, you can’t simply dump all the pieces out on the table and begin connecting them. Instead, you sort out the few odd pieces that you have. Then you search for the rest.

When you write someone’s biography, it’s like assembling a puzzle. But if that person lived in the mid-nineteenth century, you can’t simply dump all the pieces out on the table and begin connecting them. Instead, you sort out the few odd pieces that you have. Then you search for the rest.

But . . . what if someone has slightly altered the few available pieces, smoothed the corners to fit his own moral doctrine? And what if there are empty spaces, missing parts you can’t find? The story of Achsa Sprague posed these dilemmas from the start.

Lily Dale is a Spiritualist community in upstate New York, and that’s where I first saw Achsa mentioned in a book that had been loaned to me. A footnote revealed “The Achsa W. Sprague Papers held by the Vermont Historical Society are, as far as I can ascertain, the only extant personal papers of a nineteenth century Spiritualist medium.” I was intrigued.

I purchased my own copy of the book and tore out the page with Achsa’s portrait—it’s also on the cover of Seven Years of Grace—and pinned it above my desk. There was something about her eyes, that steady, almost defiant gaze that challenged me to dare to look away.

Her enigmatic stare was appealing, and I felt similarities between us. Achsa was from Vermont. I had earned my MFA in Writing at Vermont College in Montpelier, and taught in the Goddard College MFA program at Plainfield. Achsa wrote poetry and I’d already published four books of poems. She was a missionary; that had been my childhood dream. I was intrigued by Spiritualism (I’d been enrolled in the Lily Dale workshop “The Personal Development of Mediumship,”) and we were both feminists, day-dreamers, progressives. She’d kept a daily journal, and I’d kept one since 1962. I was also a biographer and sensed there was an untold story hiding behind Achsa’s gaze.

I wanted to plunge into research right away, but I was in the midst of writing other books. My enthusiasm for Achsa would have to be sustained for a year or two, I thought. In July of 2000, I returned to Vermont, ready for work. I had already studied a published version of Achsa’s diaries. The originals had been purchased in the late 1930s at a Rutland bookstore by Leonard Twinem who, in 1941, offered an edited version for publication in The Proceedings of the Vermont Historical Society under his pseudonym, Leonard Twynham. Achsa’s entries began on June 1, 1849, “Once more I am unable to walk or do anything else; have not been a step without crutches since Sunday and see no prospect of being any better; see nothing before me but a life of miserable helplessness.” On her birthday, November 17, she wrote of her disillusionment: “Twenty-two years ago today, a new life sprung into existence; the earth received a new inhabitant; a spirit clothed in the garments of mortality. . . . And this is my destiny, mine. My own sad history.”

Twinem’s cunning edits drove me crazy. After “my own sad history,” he followed with an ellipsis (indicating sentences deleted) and then, “Mr. Woods people want me to teach school there this winter, but don’t think I shall.” Achsa’s rebirth was suddenly revealed in 1853 when “After a long, almost a three years silence again I unfold these pages, once more to trace upon their surface the thoughts of a long-tried heart.” A miraculous transformation had occurred (had Twinem omitted that part?): Angel guardians had cured Achsa and obtained her promise to spread the word of Spiritualism and the fact that we do not die.

I found Achsa’s grave at the Plymouth Notch cemetery. The words “I Still Live” carved on her blue marble tombstone were nearly hidden by weather stains and spreading lichens. I realized that, by writing her biography, I could help Achsa still live.

I hired a fellow Vermont College MFA grad, Caroline Mercurio, to join me in viewing the extensive collection of Achsa Sprague materials in the Vermont Historical Society archives. There were so many letters sent to Achsa, all written with quill pens and difficult to decipher. Caroline photocopied each letter and sent packets to me throughout the next year. I received each thick envelope with the excitement of a child at Christmas, requiring months of quiet to painstakingly read and transcribe each. An important breakthrough occurred when Caroline noted that letters on blue stationery from a John Crawford stood out from the rest. When I placed all the Crawford letters in chronological order, an unforeseen dimension was evident: until that moment, no one had known of the intense romantic relationship that Achsa developed with this wealthy, erudite man whom she called her “Evil Genius.” Achsa’s correspondence with him was frequently quoted in his passionate replies, so the provocative exchange between the two was unmistakable: another clue in her untold story.

There were other challenges in the archival files: scraps of paper with no attributions, rough drafts of letters, even a note in mirror writing. From the abridged diaries, newspaper columns, letters, and disparate notes, I began to trace Achsa’s travels and emotions. A posthumous collection of her poetry, The Poet and Other Poems published in 1864, also contained a play with a character called “Miss Raymond.” Unmistakably Achsa, she was an improvisatrice with similar physical attributes and mystical powers.

Not unlike others, modest in her guise,

A soul of goodness beaming from her eyes.

Yet nothing marked to tell the power within,

That, when aroused, so many hearts must win.

She’d mingle in the crowd, and scarce be seen,

With thoughtful face, and modest, graceful mien;

But when her harp is once within her hands,

And rapt, inspired, before the world she stands,

A glow spreads over all her face and brow

Before which others cannot fail to bow. . .

After I returned from Vermont that summer, I was occupied with radio interviews all across the country for another of my books. In my journal, I wrote “The days pass too swiftly and I can’t work fast enough.” I was still seeking the original Sprague diaries, writing letters and making calls to investigate their location. I spent a week at our rustic lakeside cabin with my husband, and in the silence I thought more about Achsa. “Now I can proceed with Achsa at my own pace with my own creative perspective—trusting, when it feels right, that it is right—and who is alive to contradict me, or question my possible communication with her spirit?”

Achsa and other Spiritualists were fond of quoting poet Alexander Pope, who popularized an optimistic philosophy:

. . . All nature is but art unknown to thee,

All chance, direction which thou canst not see;

All discord, harmony not understood;

All partial evil, universal good;

And, spite of pride, in erring reason’s spite,

One truth is clear, Whatever is, is right.

This became my mantra for the many iterations of Achsa’s manuscript that I produced thereafter: if it felt right, if my intuition captured the essence of her story based my research, then the perspective could be perceived as accurate. (If not, perhaps she’d have me struck by lightning!)

In February, 2001, I began a rough draft of the book. We drove east again that summer. At Lily Dale, I searched the cluttered library of the National Spiritualist Association of Churches and found a collection of obscure Spiritualist newspapers for which Achsa had written her “By the Wayside” column, opinionated articles, children’s stories and poems. In The Banner of Light I found a first-person account of a friend’s presence at Achsa’s deathbed. On the last day of our visit, I climbed up into the creepy attic to search among bat and mouse droppings for the missing diaries, with no success.

I placed a marble at Achsa’s grave because it reflected my face and the sky. Eliza Ward, who’d been in the original Sprague home prior to its razing, drew for me a floorplan indicating the location of rooms and even the privy. She also gave me a tiny tintype of Achsa as a girl. I visited folks at the Woodstock Historical Society to explore a fascinating record of Spiritualist activity during Achsa’s time, and we went up to the Rokeby Museum in Ferrisburgh, where Achsa had lectured in 1856.

Without access to Achas’s lost complete diaries, my plan was to interweave the abridged diary with excerpts from letters and articles and my own narrative to tell her story. I had decisions to make about voice, tone, and organization.

A huge breakthrough occurred with my discovery of Spirit History, a website intended to “compile and preserve Nineteenth-Century American Spiritualism’s Fading Records.” This remarkable resource was created by John Buescher, who was then involved with the Voice of America. Although we’ve never met, John became a mentor whose contributions to Achsa’s story were vital, furnishing a depth and breadth that would have been impossible without his scholarship.

I had, by then, also become obsessed with Leonard Twinem, a/k/a L. Leonard Twynham. I was convinced there must be some way to track a museum or a relative who might hold Achsa’s actual diaries, plus additional materials Twinem had crowed about. He’d claimed in the 1941 Proceedings that he was “contemplating the publication of a volume which will include her prose and verse and a long biographical sketch,” as he also possessed “a vast quantity of manuscript material, verses and essays, which await publication. Among her unpublished manuscripts is an autobiographical poem of 162 pages, which she composed in six days, when in such a nervous state that the spinning wheel, latches, and roosters were all muffled for her peace of mind; and also a poetic play of 75 pages dealing with the Biblical story from Eden to Calvary.”

Eccentric and parsimonious to a fault, Twinem told the Vermont Historical Society, “for the work to date I charged only the secretarial costs for transcription; and gave lots of my own time and energy aside from the large amount I originally invested in the box of Sprague items I have in hand. So I feel my generosity is exhausted. Hence I give nothing away.”

Twinem’s brother Francis donated the box of Sprague correspondence to VHS in 1976, a decade after Leonard’s death, but there had been no other “literary remains” of Achsa Sprague in his possession, and he had no knowledge of them. Paul Carnahan, director of the VHS Library, said that the disappearance of the Sprague diaries and associated papers was one of the great mysteries of Vermont history. They, too, had searched everywhere, and no one in the state had a clue as to their whereabouts.

The diary search began to consume time that I should have spent writing. For example, when visiting a nurse practitioner for an annual appointment, I even mentioned my exasperation to her! “Nothing happens by accident,” she assured me, and that night she told her friend of my diary quest. She passed along the resulting clairvoyant insights, which I dutifully passed along to Paul:

“I see a red brick building. The building is two stories. It has four steps up to the front door. The building has 241 associated with it. That might be a building number or a zip code or something. There may be more numbers but that’s all I get. You go through the door and it’s in the back corner of the room. It’s a storeroom or something and it isn’t used anymore. They’re gonna have to dig. It’s more than just one and they are little books.”

Paul and Caroline then searched the cobwebbed basement of a nearly abandoned building, a warehouse where a bookshelf tipped over, spilling old copies of the 1941 Proceedings booklets. So Achsa’s diaries were there, just not the originals we wanted. Paul had been especially intrigued since 241 was the telephone exchange in the town where the red brick warehouse was located.

Vexed and frustrated, I contacted every archived collection of women’s diaries at colleges and universities in the United States. I wrote to auction houses, antiquarian booksellers in New England, historical societies. Nothing showed up.

Twinem was also a Presbyterian minister, deposed from the ministry in 1938 and restored in 1945 (what happened there? The Episcopal diocese of New York had no idea but suggested that perhaps he “dumped the Sprague papers before being restored to the Ministry,” and perhaps “his interest in Spiritualism was why he was deposed in the first place.”)

In my exhaustive search, I acquired copies of Twinem correspondence. In a 1937 letter to the American Antiquarian society he commented about a prospective Sprague biography, “the task of assembling the material—sorting and selecting—from a jumble of letters and manuscripts, in preparation of a volume, is enormous.”

I Googled-searched Twinem, then Twynem, and obtained only a bit of useless data from the resulting letters I wrote. I requested a copy of Leonard’s will from the Probate Court of Sharon, Connecticut. A copy of his wife’s will. Nothing. I looked up Twinem’s wife Mary on Ancestry.com and wrote to a woman who’d said Mary lived with their family prior to her death. In fact, her mother had held Mary Twinem in her arms when she died, but only a few scrapbooks of Leonard’s had been in her possession. The Twinems had no descendants and nothing in the scrapbooks related to Achsa.

I finally had to admit I’d struck out.

Working with what I had, I compiled significant timelines: one for Achsa, another for John H. Crawford, and a third for Achsa’s sister, Celia Sprague, who had moved to Fond du Lac County, Wisconsin, in 1853 and eventually married John Steen, a farmer from Oakfield. I hired a genealogist to help with Celia. We found the Avoca cemetery near Oakfield, and Celia’s grave next to that of her husband. Her tombstone had only her first name and this quote from Les Miserables:

“Kiss me on the forehead when I am dead and I shall feel it.”

Prior to this, Celia’s date of death and location of her passing were unknown.

In 2003 I was awarded the Weston A. Cate Fellowship by the Vermont Historical Society, which helped with costs associated with my research.

On a rainy day in August, 2004, I spoke to a standing-room-only crowd in the Plymouth Notch schoolhouse, where Achsa had taught. With tears in my eyes, I read her poem, Lines Written in a Schoolroom:

“The school-room is deserted now,

The happy children gone,

and silence rests upon the spot

So strangely, sadly lone…”

The rain let up when we held a short ceremony at her grave, then it started raining again.

It has been twenty years since I first learned about Achsa Sprague. Since then, I’ve published four other books. Between each project, I returned to Achsa. First, I revised a scholarly, footnoted, third-person manuscript from 2004 that now rests in the Vermont Historical Society Archives and contains everything remotely relevant, down to the last painful detail. Next, I tried for a more engaging third-person version. Then I let Achsa tell her story. First-person was fiction, but it was liberating to let her have her say! Finally I settled on allowing Celia to speak, since many letters from her had been kept in Achsa’s files. Celia’s point-of-view was historical fiction, but I lived in Wisconsin, knew its history and I could “imagine” details of Celia’s life. In turn, she would be able to depict Achsa with personal details as no one but a sister could. Celia could also help me create missing pieces of the puzzle. She had once told Achsa, “I can now say with the poet “whatever is, is right” so henceforth you may expect me to submit to whatever comes & then do as I best can.”

Then the long-sought original Achsa Sprague diaries appeared on eBay in May, 2013. Where had they been?

The seller said the diaries had been purchased at an auction in New York. “They seemed to be very interesting diaries but once we found out who the author was, then we did think they were special.”

Special? Paul Carnahan declared the diaries invaluable! The two of us offered separate bids each day to acquire them if we possibly could. Alas, the final offers grew far beyond our combined reach. Someone out-bid us for a total of $4,997.00 on May 16, 2013. Attempts to contact the purchaser since then have been for naught.

Seven Years of Grace is based as closely as possible on truths I have been able to acquire, and where there were missing pieces of the puzzle, I endeavored to capture the essence of what most likely transpired. (“Whatever is, is right.”)

This was scribbled while I sat near Achsa’s grave one afternoon:

“You ask for a poem this is what I give you for its stead you are my voice and being, lightness itself shall guide you out of shadows and give you direction. . . we are sisters we share stories this is my secret and yours, our sorrows are similar and our loves as well. . .”

Sara Rath

Sara Rath’s books published by the University of Wisconsin Press include three novels— Star Lake Saloon & Housekeeping Cottages, Night Sisters, The Waters of Star Lake—and a biography: H. H. Bennett, Photographer: His American Landscape.

Her novel Night Sisters includes scenes at the historic Wocanaga Spiritualist Camp in Wisconsin. See a video interview with Sara about Night Sisters and Wocanaga.

ularly received praise and thanks from the authors with whom she worked, and her mentoring of the journal’s graduate-student editorial assistants was much appreciated. The editorial office staff of the journal and staff at UW Press wish Mary the very best.

ularly received praise and thanks from the authors with whom she worked, and her mentoring of the journal’s graduate-student editorial assistants was much appreciated. The editorial office staff of the journal and staff at UW Press wish Mary the very best.

Kathryn A. Remlinger

Kathryn A. Remlinger